Long-tailed Duck (Clangula hyemalis): vulnerability to climate change

Evidence for exposure

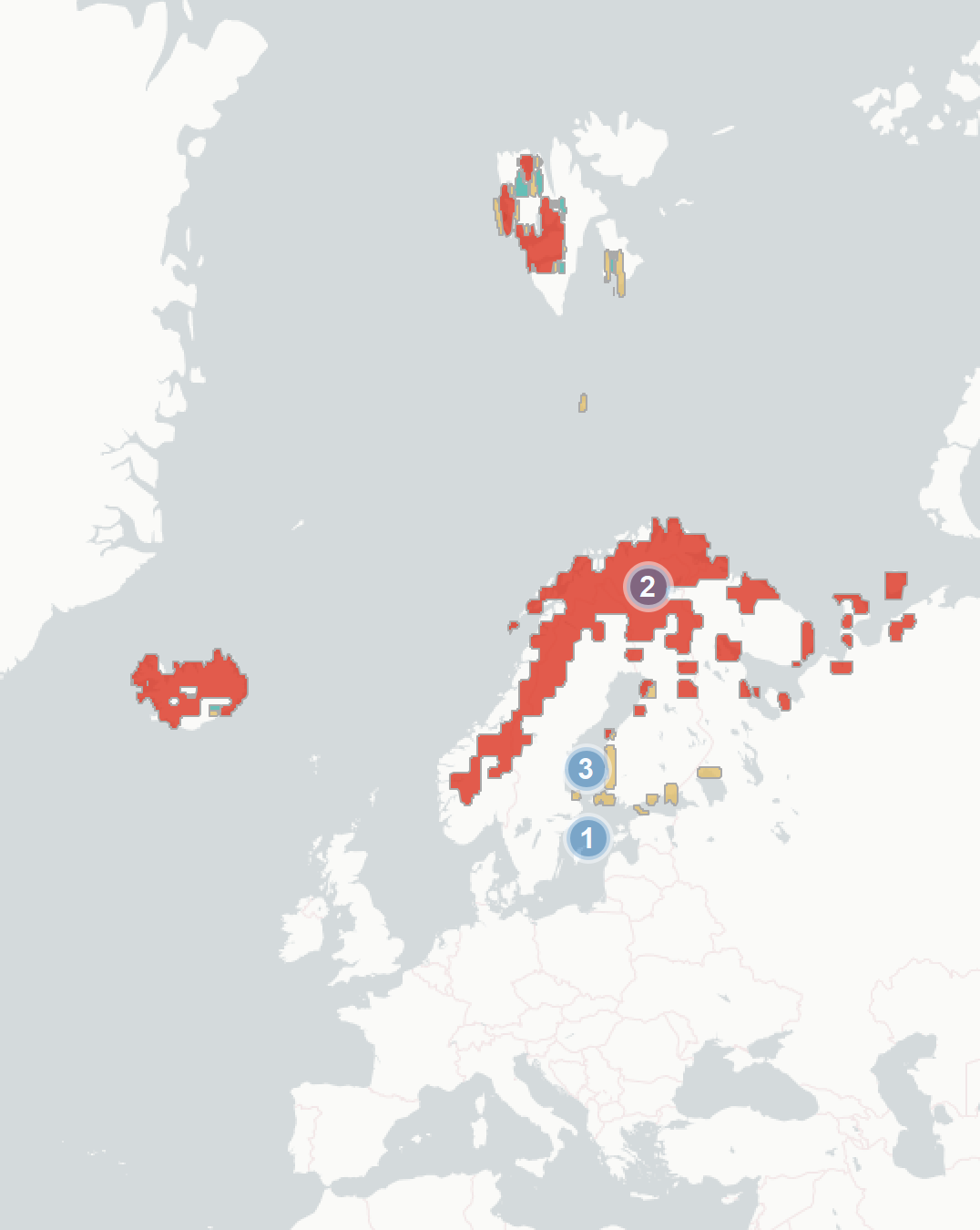

Potential changes in breeding habitat suitability:

-

Current breeding area that is likely to become less suitable (89% of current range)

-

Current breeding area that is likely to remain suitable (8%)

-

Current breeding area that is likely to become more suitable (3%)

Current impacts to Long-tailed Ducks attributed to climate change:

-

Negative Impact: Wintering populations in Europe have declined due to climate change-driven changes in predation in breeding areas outside of Europe.

-

Negative Impact: Range expansion of red foxes following milder winters has led to predation of ducks much further north than previously, and may be threatening the viability of northern populations.

-

Neutral Impact: Competition with non-native gobies has caused long-tailed ducks to switch prey, though there has been no observed change in mortality or condition. Goby invasion may have been assisted by climate change, though currently this is speculative

Predicted changes in key prey species:

No key prey assessment was carried out for this species.

Climate change impacts outside of Europe

-

Species is known to be sensitive in North America to changes in sea temperature, fluctuations in NAO, and, in particular, the presence of sea ice. Such changes cause year-to-year changes in their wintering distribution across America. A decline in sea ice is likely to result in a range shift of wintering populations, and it is possible that such a redistribution has already occurred in the Baltic.

Sensitivity

-

This species is numerous and has a large circumpolar range, but surveys suggest it is declining rapidly especially in the Baltic, most likely due to heavy bycatch. Any additional pressure from climate change is likely to exacerbate these declines.

-

Several populations of long-tailed ducks are strongly reliant on Mytilus edulis for much of the year. Mytilus is known to be sensitive to climate change, and warmer conditions are likely to result in lower quality prey. The consequences for long-tailed ducks are uncertain, but are very likely negative.

-

Key wetland breeding habitats across the Arctic are rapidly disappearing or changing. The overall impact on long-tailed duck populations is unknown, but very likely to be negative.

-

Often nests on low lying areas near water, sensitive to flooding due to increased rainfall or wave-action. Any increase in intensity or frequency of storms is likely to impacts breeding populations

-

Long-tailed ducks tend to winter in large groups in relatively small areas, so are vulnerable to mass mortality through extreme events. Even localised climate change impacts may have large consequences on the population as a whole.

Adaptive capacity

-

Studies have found low migration connectivity between populations and low differentiation (populations will mingle during non-breeding season). This may make populations more resilient to climate change, as immigration to support populations is more likely.

-

Species has a very broad diet that varies depending on season and population, in the Baltic they have rapidly adjusted their diet in response to changes in prey availability. The loss of one prey species is unlikely to impact population, though note that some population may still be reliant on one or a few key species at some times of the year

-

Long-tailed ducks either abandon or skip breeding in particularly unsuitable years, preserving resources. This could be adaptive if conditions become more variable and ameliorate the impact of poor breeding conditions

-

Long-tailed ducks generally have high site fidelity and are unlikely to shift breeding areas quickly in response to climate change