Common Eider (Somateria mollissima): vulnerability to climate change

Evidence for exposure

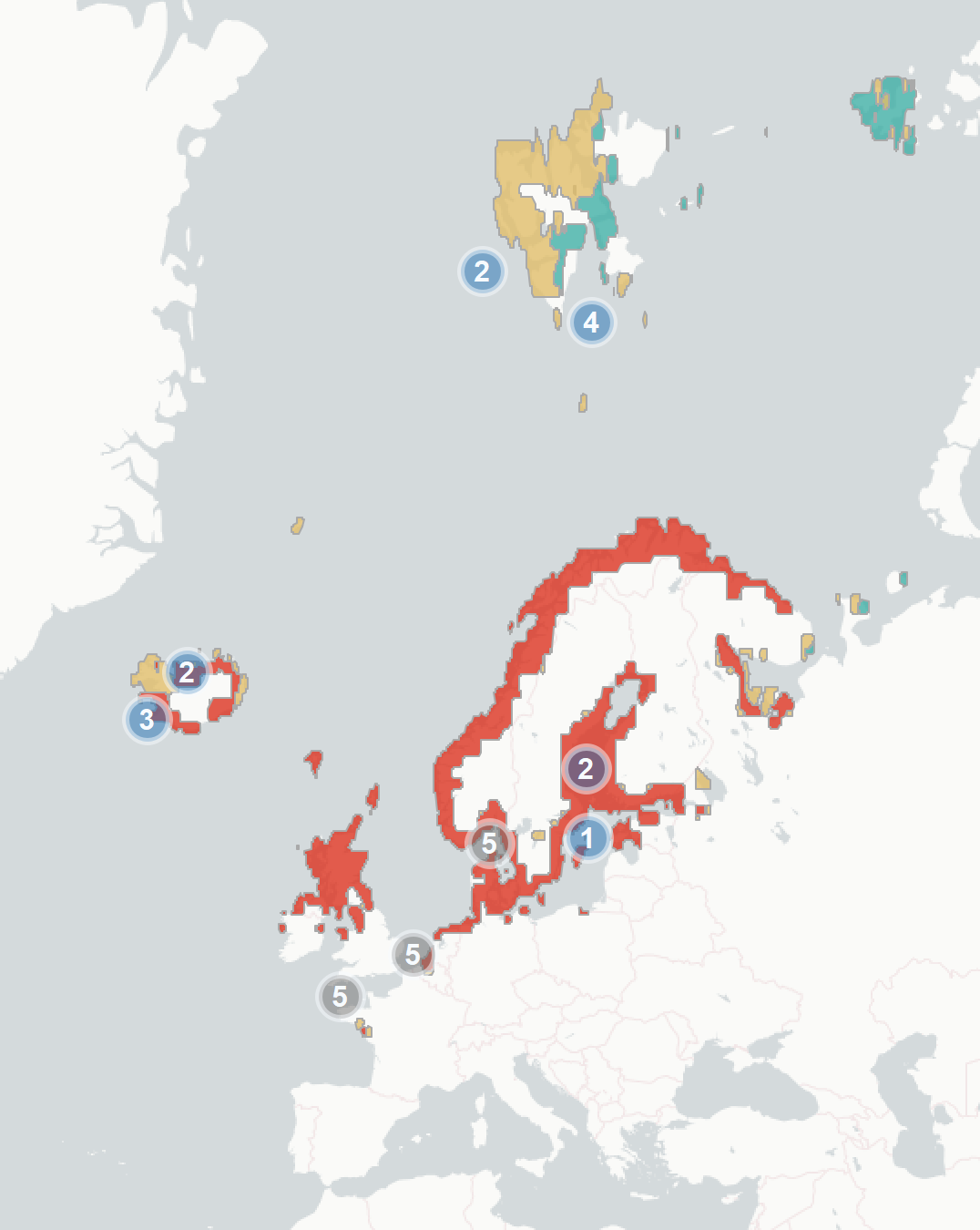

Potential changes in breeding habitat suitability:

-

Current breeding area that is likely to become less suitable (74% of current range)

-

Current breeding area that is likely to remain suitable (18%)

-

Current breeding area that is likely to become more suitable (8%)

Current impacts to Common Eiders attributed to climate change:

-

Negative Impact: High precipitation and wind intensity have reduced chick survival, likely through direct mortality from exposure and due to increased foraging difficulty. Extreme precipitation and wind events are both predicted to become more frequent with climate change.

-

Positive Impact: Milder winter and summer weather generally results in better adult condition, and therefore better breeding success. In some areas this has resulted in local populations increases.

-

Neutral Impact: Eiders have shifted their phenology in response to milder winters and lay earlier.

-

Negative Impact: Due to a lack of sea ice driven by climate change, polar bears are becoming more numerous around bird colonies during the summer and are more heavily predating on eider populations

Predicted changes in key prey species:

-

Key prey species are likely to decline in abundance along the coast of Brittany, the coast of Belgium and along the south coast of Norway and Sweden

Climate change impacts outside of Europe

-

Known to be affected by climate change in other parts of their range. They suffer increased predation from arctic foxes due to prey switching following a collapse in lemming breeding cycles in northern Canada.

-

In addition Canadian populations have suffered due to changes in weather in the breeding season, especially increased rain, either directly through exposure or indirectly through changes in predation.

-

Across Canada and Alaska many populations are benefiting from shortened duration and extent of sea ice, which improves foraging conditions.

Sensitivity

-

This species has a large population, a large range, but is declining in several parts of its range. Known to be decreasing rapidly in the Baltic, climate change could be one of the underlying causes but this is uncertain

-

Often nests on low lying coasts, sensitive to flooding due to increased rainfall or wave-action. Any increase in intensity or frequency of storms is likely to impact breeding populations

-

Eiders have a varied diet of invertebrates but many populations are strongly reliant on Mytilus edulis for much of the year. Mytilus is known to be sensitive to climate change, and warmer conditions are likely to result in lower quality prey. The effect of this on eiders is uncertain, but is very likely negative.

-

Eiders tend to winter in large groups in relatively small areas, so are vulnerable to mass mortality through extreme events. Even localised climate change impacts may have large consequences on the population as a whole.

-

Eiders have shown declines during historical changes in sea temperature and fluctuations in NAO, particularly affecting the survival and distribution of wintering populations. They are likely sensitive to future changes in marine ecosystems.

-

Eiders are particularly sensitive to disease outbreaks, bad years can claim up to 99% of offspring, and outbreaks seem to have a long term effect on female survival rate. Any change in disease dynamics due to climate change is likely to have significant impacts

-

While climate change is likely to be positive for some populations, it does not mean that populations will necessarily increase in response to climate change. Recent research has found other pressures, in particular predation by native and non-native predators, essentially override the positive effects of climate change, which appear to be small overall.

-

This species has a long generation length (>10 years), which may slow recovery from severe impacts and increases population extinction risk

Adaptive capacity

-

Eiders either abandon or skip breeding in particularly unsuitable years, preserving resources. This could be adaptive if conditions become more variable and ameliorate the impact of poor breeding conditions

-

There is low migration connectivity between many populations in Europe (though this is not universal), and many populations will mix in the non-breeding season. This could be adaptive, as low connectivity is associated with greater flexibility and higher responsiveness to change

-

Female common eiders are typically highly site faithful to breeding sites, extreme breeding philopatry of female ducks means it is unlikely populations will change or shift in response to climate change

-

While some populations appear to have changed their phenology, other studies have found changes in laying date are not related to weather conditions. Plasticity seems to vary between populations

-

Historically eiders have expanded their range, and colonised new areas such as Ireland and NW England in the early 20th century. This suggests if populations grow and conditions are suitable then eiders can colonise new areas